Introduction

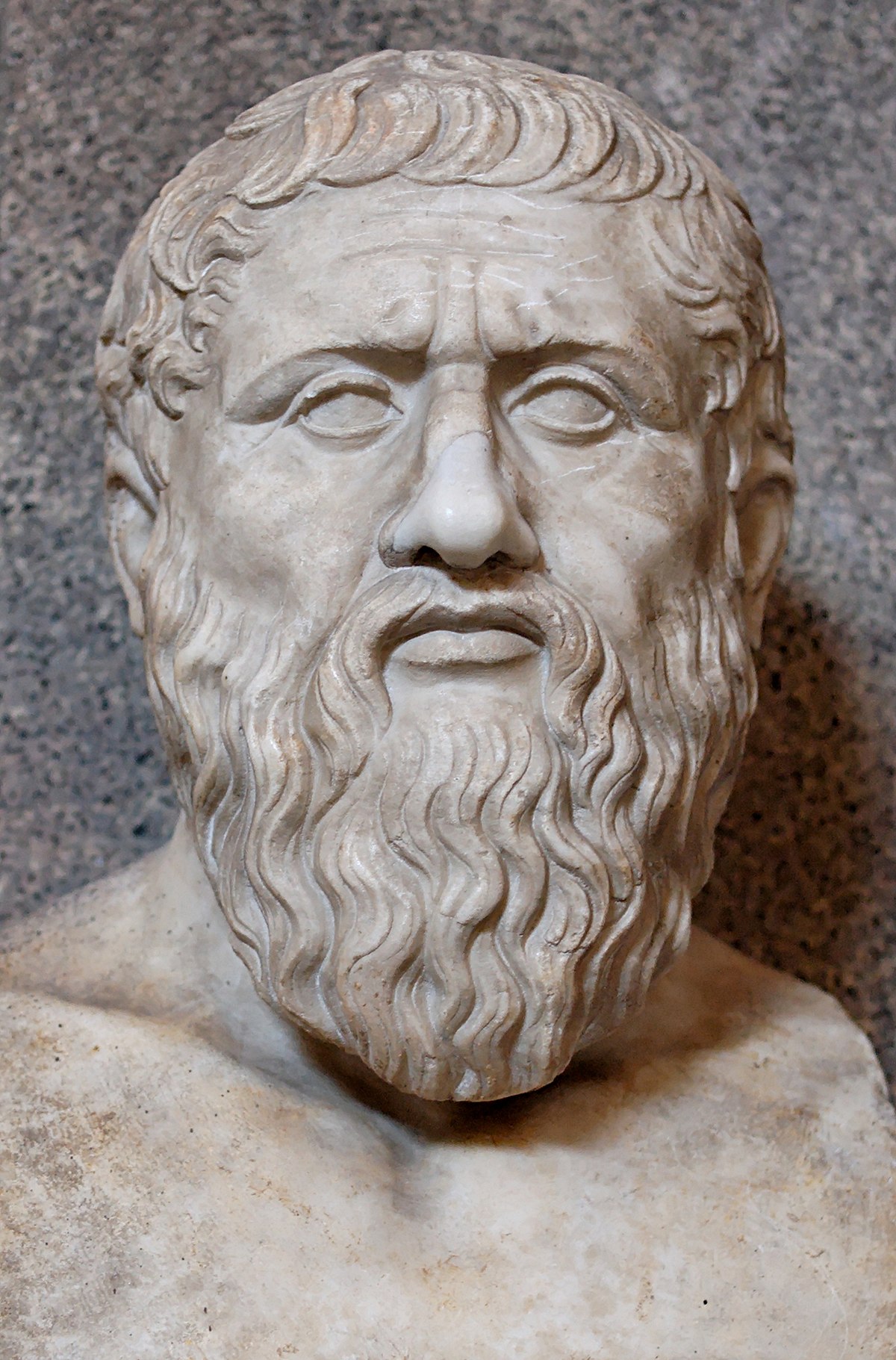

The theme of beauty is one of the great topics Plato analyzes in various dialogues, primarily in “Greater Hippias or Dialogue on Beauty” (390 BCE); in “The Apology of Socrates” (393–389 BCE); in “The Symposium” (385–370 BCE); and in “Phaedrus or On Love” (370 BCE).

For Plato, beauty is transcendent and indefinable. It is intelligible: it is accessed through the intellect, without mediation by the senses.

In “The Apology of Socrates”, Socrates is condemned for impiety and for corrupting the youth, as teaching them to think turned them into his disciples. Socrates opposes the art of deception and the pseudo-beauty of sophist rhetoric with discourse based on truth.

For Plato, the world we see, the sensible world, is not the real world. We are like prisoners locked in a cave (The Republic), where we only see shadows that appear to be realities but are mere imitations of the truth. Truth is discovered only through intelligible realities, through “ideas” accessible by the spirit. For Plato, beauty itself is intelligible.

Is there a definition of beauty? This is one of the questions Socrates poses in the aforementioned dialogues.

Dialogues: “Greater Hippias”, “The Apology of Socrates”, “The Symposium”, “Phaedrus or On Love”, and others.

Beauty is transcendent. Indefinable. Plato intertwines the concepts of beauty and truth.

Beauty is intelligible: it is accessed through the intellect, without mediation by the senses.

Greater Hippias:

This is Plato’s first dialogue addressing “beauty.” Hippias is one of the most famous sophists of the time. Socrates meets him and asks, What is beauty? Hippias provides three answers:

- Beauty is a beautiful maiden.

- Socrates replies: The question is not whether someone or something is beautiful, but what beauty itself is.

- Beauty is gold.

- Socrates responds: Gold is not exclusive to beautiful things; there are beautiful things that lack this element.

- The most beautiful thing in the world is being rich, enjoying good health, being honored, reaching old age, hosting a beautiful funeral for one’s parents, and receiving funeral honors from one’s children.

- Hippias rejects the demand to clarify what beauty means. He fails to distinguish beautiful things from transcendent “beauty.”

A key question arises: Is beauty inseparable from the pleasure it provides?

Paradox: It is difficult not to associate beauty with pleasure. However, according to Platonism, understanding beauty in terms of pleasure distances us from its essence. The concept of beauty that Plato seeks goes beyond the physical. In Greater Hippias, Plato does not succeed in conceptualizing beauty.

The Symposium:

Socrates is invited to a feast where guests are asked to answer the question: What is love?

- Agathon: Love desires beauty.

- Socrates replies: Then, does love lack beauty? Does it not possess it? For Socrates, love is the pursuit of absolute beauty. This pursuit follows a progression, moving from the sensory to the intelligible and eternal.

- Alcibiades: Describes platonic love as the pursuit of the ideal, free from all sensuality.

For Socrates, beauty is true, permanent, universal, and absolute. Beauty is an eternal reality, unchanging. It is a Good. The power of the good lies in clearly and evidently understanding similarities and differences. “Beauty is simple, pure, and unadulterated.”

Phaedrus:

The first part of this dialogue focuses on love for beauty. The second part addresses rhetoric and truth.

Socrates meets Phaedrus, who is reading a speech by Lysias, arguing that it is better to choose as a lover someone who does not love you rather than someone who does. For Phaedrus, Lysias’s speech is beautiful and grand. For Socrates, it is empty. Socrates insists on defining what one is discussing: What is love? What is it to love?

For Socrates, love is a form of desire. Yet desire has two aspects:

- The desire for pleasures devoid of reason.

- The aspiration for what is better: temperance.

The key for Socrates lies in Reminiscence: the idea of beauty that the soul once contemplated in its splendor in another life is revealed to our eyes (Timaeus).

The love of beauty opens the soul to the world of ideas and the contemplation of the good. The lover’s role is to guide the beloved toward sublimated love, intellectual communion, and the contemplation of ideas.

Socrates contrasts the sensible world of appearances with the intelligible world, which leads to true knowledge through science. For Plato, Science has a specific meaning: it does not concern material reality but ideas. Mathematics, geometry, and arithmetic guide us to higher realms, accessible only to the intellect.

The second part of the dialogue focuses on love for truth. Socrates argues that the quality of a speech depends on the speaker’s knowledge of the subject. Phaedrus counters: This is not how sophists understand it. A good orator does not need to know what is right or wrong because persuasion does not depend on truth.

The debate has two axes: knowledge and truth versus opinion and appearance.

For Socrates, rhetoric is an art if it is based on truth. Deprived of truth, it becomes the art of deception. Socrates condemns sophistic rhetoric, which uses rhetorical tricks to persuade the audience at the expense of truth. Instead, he proposes a rhetoric of truth.

For Plato, ideas are reality. He does not speak of beautiful things or virtuous actions but of Beauty and Virtue themselves. For him, ideas are the model for everything. A beautiful object is merely an approximation of the idea of beauty it seeks to represent.

Freemasonry and Beauty

From a Masonic perspective, ritual can capture the idea of beauty, allowing the experience to extend beyond the ritual itself. In the ritual, one glimpses a certain order in creation, reflecting traits of the Idea it represents.

In the Lodge, we find three spaces defined by the pillars of Wisdom, Strength, and Beauty, the latter associated with Harmony. The essence of beauty is eternal, and the harmony of the universe is intangible.

Freemasonry: Humanity, or the microcosm, reflects the macrocosm.

There are connections to Platonism: the One as the whole; the existence of an intelligible world and a sensible world; and humanity as the link between the divine and the earthly, among others.

ACP